Fires played a significant role in shaping Ottawa’s history, with some of the most destructive ones occurring between 1870 and 1900. As a result, large parts of the western suburbs and other areas were destroyed. In 1916, a mysterious fire consumed several landmark buildings, including the Russel Hotel and the old city hall. In 1979, flames engulfed the Rideau Gentlemen’s Club. What was this club like, and how did Ottawa’s elite and wealthy youth spend their free time in Canada’s capital? Ottawa Ski provides an in-depth look.

The Establishment of the Gentlemen’s Club

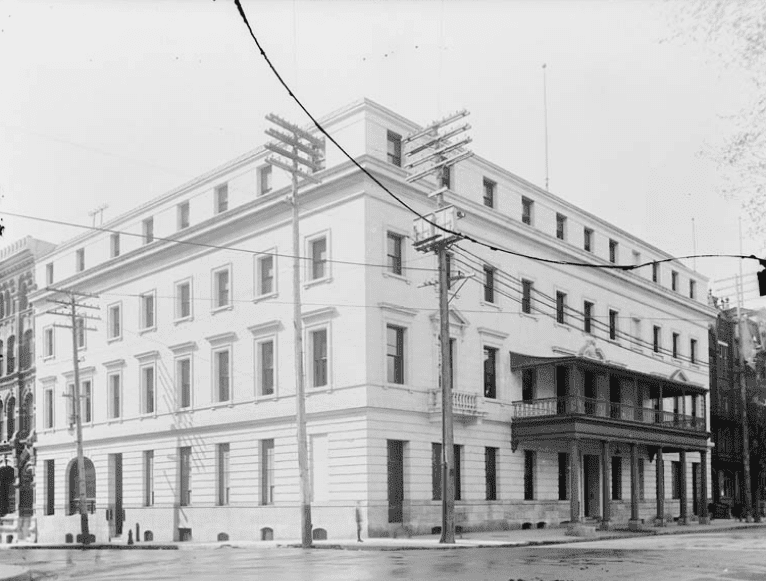

Early photographs of the Rideau Club, located at the corner of Wellington and Metcalfe Streets, showcase one of Ottawa’s most exclusive private clubs of the time. The club was founded in 1865 by Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. It took another 14 years before the club admitted women, but more on that later.

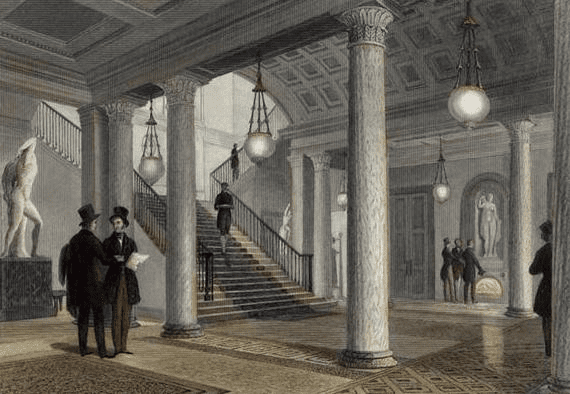

What kind of club was it? It was a prime example of a British gentlemen’s club, modeled after those that flourished in Victorian London. Young gentlemen sought entertainment and an escape from domestic life. The club served as a social venue for its guests. Some entrepreneurial members used it for business negotiations or networking to improve their social status.

In 1865, Ottawa had many taverns and bars, but no establishments catered to a more refined clientele. Macdonald and Cartier took advantage of this opportunity. The Rideau Club became a place where Ottawa’s capital elite could engage in leisure and other activities.

Club Rules and Regulations

Without rules, the club could not have maintained its exclusivity. Interestingly, its statutes and regulations were borrowed from the St. James Club in Montreal, which had been established earlier in 1858. Looking at the list of members, one might mistake it for a roster of the city’s most influential figures. The Rideau Club was one of the oldest private business clubs in Canada.

Sir John A. Macdonald was the club’s first president, followed by Sir Cartier. The membership list included Ottawa’s business elite. The rules dictated a strict dress code—business attire was required, with an optional tie.

The club changed locations several times:

- Initially, it was at 200 Wellington Street, the site of Ottawa’s premier hotel at the time, Doran’s Hotel.

- In 1869, it moved to the Queen’s Restaurant, a site now known as the Langevin Block.

- In 1876, the club relocated again to the opposite side of Metcalfe Street. The Rideau Club Building Association purchased land from renowned Ottawa photographer James Topley and constructed a modest structure. The association allocated $4,000 for the purchase.

- By 1911, the property had been expanded three times due to the growing number of club members.

The entrance to the renowned Rideau Club faced Parliament Hill. For 103 years, it remained a home for Ottawa’s elite and an exclusive institution.

Activities and Entertainment for Club Members

The Rideau Club was essentially a “second home” for its members. It provided a space where they could socialize with friends, play indoor games, dine, and even stay overnight. The club became a central part of life for Ottawa’s wealthy men. Upon arrival, members could unwind and relieve stress. The club offered a variety of amenities:

- Dining halls

- Library

- Game rooms

- Entertainment areas

- Bedrooms

- Bathrooms and washrooms

- Private offices

A separate entrance was designated for maids and servants, hidden from public view. A waiting list existed for those hoping to gain membership.

Surprisingly, gossip was a common feature of the club. Social connections were formed, sometimes serving as a means for social mobility. One member might possess confidential information that others did not, giving them a certain edge. While casual conversations and jokes were encouraged, the club also had strict rules regarding confidentiality and member discretion.

Exclusive Membership for Wealthy Men

Men of all political affiliations were welcome, but women were not. Additionally, Jewish applicants were unofficially excluded—there were no strict prohibitions, but they were simply not accepted. Nearly a century later, the Rideau Club admitted its first Jewish members: Louis Rasminsky (Governor of the Bank of Canada) and Lawrence Freeman (a philanthropist and department store owner in Ottawa).

Women overcame this discriminatory barrier even later. The first woman admitted to the club was Elizabeth Pigott in the summer of 1979. A former member of Parliament and advisor to Prime Minister Joe Clark, Pigott gained membership just a few months before the Rideau Club was consumed by fire.

Lost and Forgotten

The four-story building was completely engulfed in flames. The fire likely started in the basement elevator shaft and spread rapidly due to the building’s dry and mostly wooden interior. The exact cause was never determined. The fire began around 5:00 PM, and by 6:20 PM, the club’s rooftop flag had caught fire.

Club members were devastated. One member described it as “attending the funeral of an old friend.”

The fire destroyed:

- Priceless records

- Artwork

- Unique artifacts, including paintings from the Group of Seven

Some items, however, were salvaged:

- A few dining utensils, plates, and engravings from the women’s dining room

- An Inuit soapstone carving used as a billiard trophy

- A collection of wine and liquor worth over $10,000, stored safely in the club’s thick stone-walled basement

Despite these recoveries, the fire claimed irreplaceable artifacts, including a 150-year-old model warship and tourism booklets valued at over $100,000.

In 1973, the building had been deemed structurally unsafe and beyond repair. Three weeks after the fire, the walls of the once-exclusive Rideau Club were demolished. The building had no insurance coverage. In 1980, club members secured a $10.5 million settlement, including interest, through a legal claim.

A Modern Perspective

After the fire, the Chateau Laurier temporarily housed the club. The compensation funds were invested in purchasing the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company building at 99 Bank Street. Each floor cost over $5 million, with an additional $3 million spent on furnishings. Ottawa’s elite gained an impressive view of Parliament Hill and the city’s skyline.

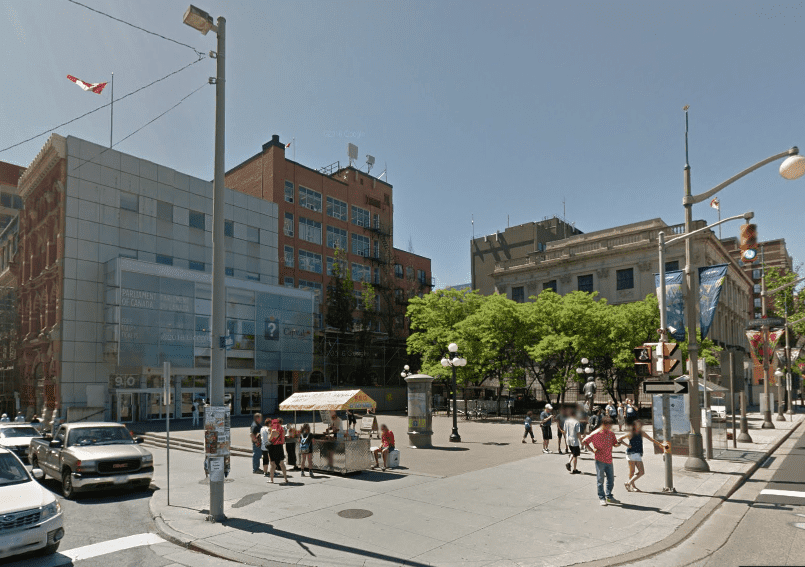

Today, an open plaza and a statue of Terry Fox—a one-legged marathon runner who attempted to run across Canada before passing away from cancer in 1981—stand on the site of the former club.

The Rideau Club continues to welcome members, expanding its network of like-minded individuals. It remains a space for business and social gatherings, preserving its traditions. The club’s motto, “Savoir Faire, Savoir Vivre,” endures, symbolizing its rich history that began in 1865 and continues despite past setbacks, including the devastating fire.